What we mean by "genius," "publishing," "intellectual property," "tests of time" and other currently debated topics

from the archives, and also from the archives

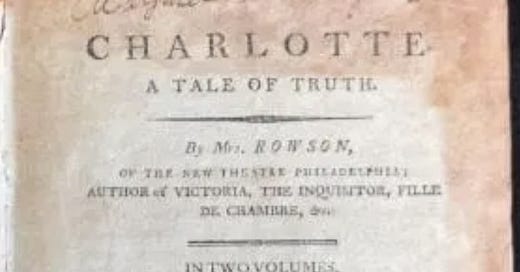

Sometimes when I read about “genius” and “publishing” and “literary fiction” and “commerce” and “standing the test of time”—topics being batted about this past week—I think about this story, below. I also think about it when we rage against AI and talk about protecting intellectual property. I published an earlier version a few years ago)

It’s 1781, and you are in Philadelphia, or maybe Boston, or Baltimore. Somewhere with a port. Your job is to sell books.

Which books, though, is the question. The people in your new country are all kinda crappy writers, or at least that’s the conventional wisdom (think self-publishing today or, maybe, more accurately twenty years ago).1 But England—now, that country knows how to fill a page with fine prose. Plus, the readers who might buy your stock have probably heard of the authors already, and successful writers, those with a “name,” sell better. 2

Luckily, there are no laws against taking English books, repackaging them under your name, and selling them as your product. That’s what everyone else in publishing is doing! They have their own editions of Sir Walter Scott novels, which the public adores, and Thomas Carlyle, maybe some Byron for the ladies. The problem is the market gets flooded quickly. Your have to get your pirated edition out first.

So here’s what you do: you send your fleetest of foot printer’s apprentice (you are a publisher as we call it now, but you are also a printer as we conceive of it today, and also an ‘indie bookseller', all rolled into one) to run (fast!) down to the docks when a boat from the former motherland arrives. That fellow needs to find a copy of Ivanhoe somewhere within the crates on the cargo deck quick as can be, and run (fast!) with it back to your shop.

There, you have already prepared everything: you have a compositor, and paper on hand, and freed up presses. The compositor, or typesetter, takes Ivanhoe, rips off the binding, and props it up on top of the upper and lower cases of type. Staring at each page, he recreates it, letter by letter, line by line, page by page, all hundreds of pages long. Sometimes he’ll stand there all night to get it done.

When his plates are done, the printer runs it under the press. Then, maybe, you send it to a bindery, and from there out to the shop floor, where people also come to buy books. Yay! You have published a copy of Ivanhoe and can sell it to all the Scott fans along the Eastern seaboard. Hopefully you have done so before J. & J. Harper (later Harper & Brothers, later Harper & Row, etc. etc until HarperCollins) got theirs out; Harper rose to prominence because they were the fastest at this ripping-off game, able to turn around pirated Scotts in a matter of days.

This is origin of American publishing: stealing works by foreign authors. There was no international copyright law, so it was all fair game (ok fine, not really stealing).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Notes from a Small Press to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.