Should You Self-Publish?

Notes:

My book proposal course starts in two months! Tell your friends! (Oh here’s a testimonial, the kind of thing I’m terrible at: “my agent was very interested to hear that I’d made more progress on my proposal since I took your class, because she says there aren’t many courses that are truly helpful out there.”)

I think I’ve happened upon a system to encourage people to become paid subscribers that I like: early access. Going forward, all posts will be for paid subscribers, and after one week they will become free to all. This is the opposite of what I’ve been doing (paywalling after posting), and a method that has worked for me: I’ve been listening to a lot of Goalhanger podcasts (The Rest Is History and Empire) and early access got me to pay for them. So if you’d like to read the rest of this post now, you can become a subscriber ($30/year); if not, it’ll be open to all next next week.

I’ve had some discussions about self-publishing recently, and while there is scads of information out there available to those who want to take this route, there may in fact be too much and folks get overwhelmed. As always, I suggest parking yourself over at Jane Friedman’s website to educate yourself.

I think anyone considering self-publishing should decide if they primarily want to be a publisher or a, well, self. That is, is your main goal to do all the things a publisher does, or more simply to make your book available to other people who might seek it out? If you don’t market or try to sell your book to accounts, for instance, you are putting it up for sale but you aren’t acting as would a publisher.

People say “you make more money” if you self-publish and that is true in that you may receive more money per copy sold than with a traditional publisher (let’s leave the question of advances aside for now), but you also need to pay yourself or others to do the things a traditional publisher would do, and you or the others might not be as good as a professional. I would think about this as one might any other DIY decision, from fixing a broken dishwasher or knitting yourself a sweater: you can do it yourself, but you have to buy the tools or yarn, and if you buy cheap supplies or aren’t great at fixing or knitting, the result likely won’t be as good.

Some people on Substack have been saying “self publish or go with a small press” as if those were similar options. They absolutely are not! A small press is, obviously, a publisher, who does things for a book self-publishing leaves you without (distribution may be the single biggest one of these).

I actually published a book that goes over much of this. It’s called So You Want To Publish A Book? and you can buy it for less than the cost of an subscription ;)

When I decided to self-publish the first book of what then became Belt Publishing, I did it the “old-fashioned” self-publishing way. We set up a website and took pre-orders, and then ordered an offset print run, the cartons of which lived in my garage. We set up an Amazon Advantage account and received and fulfilled orders from them. We mailed all the copies out ourselves (media mail is a silent boon to anyone choosing this method). I don’t think many choose this route for self-publishing, but it’s probably the way to profit the most, assuming you are publishing a book that has the potential to sell well.

For a few years, Belt offered hybrid publishing services. We took on clients for whom we would proofread, design, get barcodes, enter metadata, and distribute books on IngramSpark. Those services cost clients money, but they got their money’s worth, in that the books were professionally designed and distributed. However, we did not offer marketing services, which is what you need if you want your book to sell copies beyond friends and family. No matter how many times some people are told they are unlikely to sell many copies, many of those same people insist that their book is special and different and will, indeed, sell boatloads, even without marketing. (I’d tell you now that your book is not special and different but you wouldn’t believe me anyway.)

There are two main companies that most people who self-publish today use to have their books distributed and made available to buyers: Amazon and Ingram. Both are ginormous, monopolistic conglomerates. If you use the services provided by Amazon, you will likely make more money per copy sold, but you can only sell the book through Amazon channels. If you use Ingram, your book can be bought by other accounts: independent bookstores, Barnes & Noble, etc. You will likely make less money per copy sold. It will also be very hard to get any of those accounts to order your book, but they will be able to.

Related to the last point, something that many people seem not to understand: having a book available to order is not the same thing as deciding to stock a book. B&N may be able to order a copy of your book through Ingram, but that does not mean they will. I find people tend to understand this better if you use other consumer products as examples: your bodega might be able to order your favorite flavor of LaCroix, but that does not mean they will. The question they will ask is if anyone who isn’t you might buy it, and if it is worth the shelf space.

Another seemingly obvious point that many seem not to understand is that retailers buy products at wholesale prices. Let’s go back to our bodega. They will order cans of Coke for, say, 50 cents, and sell them for, say, $1.50. They need to make money—they need to pay stocking fees, and rent, and labor, and electricity, and buy refrigerators. I think most people understand that. Books are the same! All book retailers pay wholesale prices, no matter the scale: Amazon buys Penguin Random House bestsellers for less money than the list price. Your neighborhood indie buys a small press book for less money than the list price. The amount of the discount will vary: bigger fish, be they wholesalers or retailers, get bigger discounts, because they move more product and negotiate better terms. So no one whose business is selling books is going to pay $20 to sell your $20 book. 2

If you use Ingram to self-publish, you need to set the discount that retailers will get if they stock your book. The better the discount the more likely they will be to order. Also, the less you receive per copy sold. (This is the same calculus traditional publishers must do.)

Book publishing has an antiquated, frustrating returns policy. I’ve written about it many times in the past, but basically, retailers can return books that are unsold for full credit or refund, often many months later. If your book shows up on their ordering dashboard are “nonreturnable” they are much less likely to order it.

All this leads me to the question of who should be taking the self-publishing option:

People who enjoy and are good at marketing. Influencers are the obvious folks here, but there are scads of other people who are savvy about this and find it an energizing challenge.

~and~

People who are willing to put money into the book to have a great cover, a clean, proofread text, and experts to help them navigate distribution and accounts; people who, as with me that first time, who want to teach themselves all the ins and outs of being a publisher.

~and~People whose book might sell well, because it is in a genre that is embraced by readers even when self-published (romance, business, and books on niche topics that have a very easy-to-reach core audience come to mind).

~or~

People who just want their book available should anyone happen to want to read it. They don’t expect to sell more than a few copies, but they want the book there for posterity or as an accomplishment or for some future time when it might be found again (writers of family histories, literary fiction, and memoirs come to mind here.)

The group in 1, 2, and 3 should use Ingram; those in 4 should probably just go with Amazon.

I hope this is useful and helpful to some of you! If you have questions or comments please do reply below! I’ve left out as much as I’ve covered.

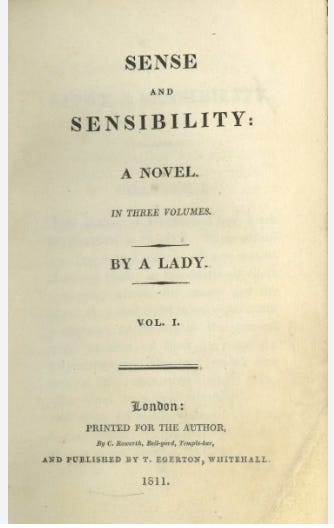

This book was self-published.

I find that traditionally published authors forget about this as well, especially when doing back-of-the-envelope calculations of how many copies they need to sell to earn out their advance. Use 50% of list price as a quick and dirty approximation of what the publisher might receive, before distribution fees, printing costs, overhead, etc. etc. for each copy sold.

These are valuable insights, thank you. The point you make about being a self publisher versus an independent one is essential, because as an indie publisher, the “self” is in effect hiring professionals to do everything aside from writing, just like a trad publisher.

I would point out that for me personally, selling a signed limited edition first and foremost via Substack was a revelation. There are readers here. And a 300-500 copy print run is extremely feasible when finding the right printer, especially if one has a vested interest in building and connecting with a literary community / creating a dialogue versus wanting to primarily make money and convince everyone about me-me-me. Writing books is a lifelong act of devotion. Those looking for an ego boost or pay check need not apply for the long haul.

What a great addition to the whole question of self-publishing! Those final points are gold. And I love the story you (partially) tell in Note #5. I can't imagine how that whole thing must have felt. Some serious emotional surfing I would guess. I self-published over a decade ago after enough suggestiveness from potential agents and editors. "Not for us. You may want to think about...."

I'd add two things to your notes: 1.) The whole self-publishing equation is in constant development and acceptance and probably will be through the rest of this decade. I say it becomes a more effective business proposition for serious writers sometime in the early 2030s; 2.) Regardless, the biggest problem with selfing is the old saw from agents/editors/publishers about "only submitting 100% never published (even on a blog or social media) work." Pardon my language, and I get the reasoning, but fuck that. I would say, every writer starting out should be required to try their hand at self-publishing. You might be successful, but you will probably mostly wind up depressed and frustrated. That's okay. The business side of all things writerly tends to be depressing and frustrating (and twisted AF). Publishers should want to work with writers who have already been down the road with a major attempt that didn't fly. Ain't nothing in the world of books that can't stand a good, long revision (everything ever published included, I'm afraid). This is so great though no matter what. Anne Trubek knows her stuff folks! That's why I subscribe...