How Should Authors Navigate AI and Publishing Contracts?

It’s a confusing time for publishing workers and authors when it comes to AI and LLMs. There are various lawsuits being brought by various groups against various companies. There’s uncertainty around licensing and copyright. There are prohibitions against anything connected to the ‘plagiarism machine’ and lots of self-righteousness on all sides. I’ve been holding off writing about this until I felt I could give a clear summary or explanation; I’m not quite there yet. But maybe I can try to clear up some common misunderstandings?

Earlier this summer I wrote a few posts about the history of copyright in the U.S., and that research definitely helped me understand the legal decisions around LLM training sets and AI that have come down recently, as well as how to conceptualize what feeding books into training sets might mean for authors and publishers. Find them here (origins of US copyright) here (earlier 19th century) and here (into 20th century). I do think this history gives publishers and authors an important grounding, and Adrian John’s Piracy is worthwhile and accessible reading for a fuller understanding.

If you want to understand the latest nuances of copyright regarding AI, I’ve just been told this report is perhaps the best; I haven’t read it yet.

For now, here are some basic things authors and people who work in publishing who are confused by what’s going on might find useful:

First: If you are an author under a contract with your publisher, read that contract. Does it say copyright will be in your name, or the publisher’s name? If it is not in your name, you’ve assigned all your rights to the publisher. But most authors keep copyright.

If you keep copyright, what do you give your publisher? Publishing rights (think of copyright as an umbrella of rights—publishing rights is under that umbrella) You have granted some of what you are entitled to under US law (not natural law! In the US copyright is a constitutional issue) to that publisher. Usually it’s for print and ebooks (sometimes audio too).

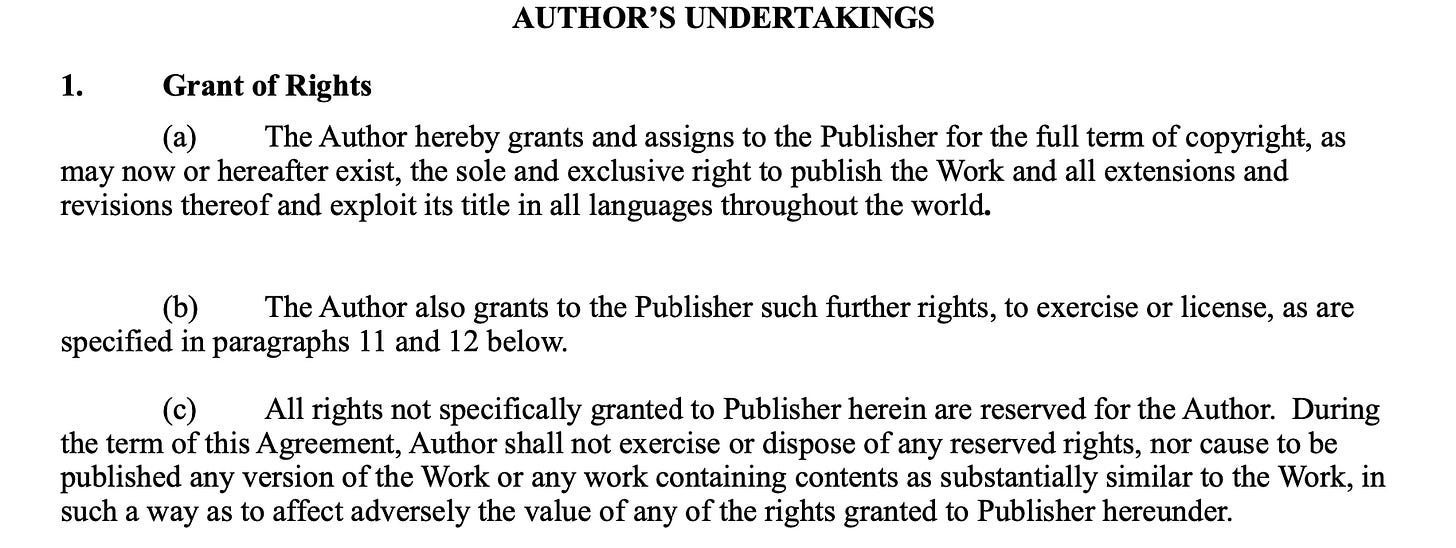

Now you’ve given away some of your rights to the publisher. But there are more rights! That you own as copyright holder! For example, this Grant of Rights clause at the beginning of a contract:

Note that it outlines other rights in addition you can grant (“specified in paragraphs 11 and 12” in this example) and additional rights reserved for the Author (section c).

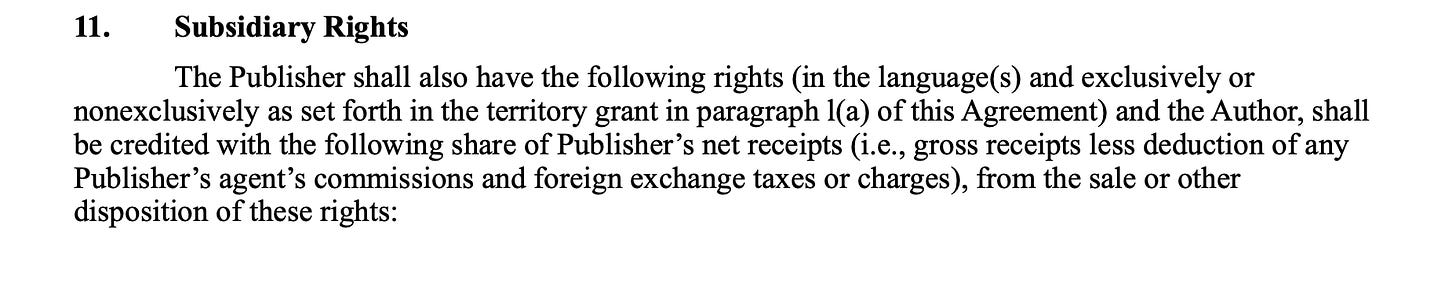

Now let’s look at those additional rights in paragraph 11, usually called subsidiary rights in contracts.

The most common subsidiary rights are foreign language, film, first serial, audiobook.

Authors can decide NOT to grant the primary publisher the right to license any of these rights. They can also agree to SPLIT the proceeds of any sales of these rights with the publisher. Or mix and match: you might say sure, you have the right to license foreign rights, but I’m going to keep film rights.

For example: A24 wants to make a film based on your book. Your contract will spell out who owns that specific right, often called Performance—you or your publisher. If it is your publisher, it will detail how much of that sweet A24 money you will get (say 75%, 50%, 25%, etc.), and if the publisher needs to have your permission before moving forward.

Okay, that we have a basic understanding of copyright as an umbrella, publishing rights as a primary subset under that umbrella, and subsidiary rights as another subset under the umbrella,

Now let’s move to AI/LLM training sets:

Rights to have a work used in a training set for a LLM are usually not spelled out in these contracts, because they haven’t existed for very long. Current legal cases notwithstanding, it seems to me these rights should be spelled out in the subsidiary list of rights, if they appear anywhere.

If a company approaches your publisher and asks to buy the rights to use to train their LLM, the publisher will decide whether or not to say yes. They are the ones who have the primary publishing right, because you signed a contract saying so.

Recent author contracts that have spelled out what might happen in this eventuality would come into play here.

If it is not spelled out, and the publisher decides to proceed, the publisher may give an author the right to opt out of having their work included—this would be like refusing to have A24 make your book into a film.

If the author does not opt out, the company may (I would say should) offer the author a split of the proceeds from such a sale, just as they would if they sold film or foreign language rights in a contract signed by the author in which they retained those rights.

Many publishers have indeed made such deals with AI companies. Here’s an overview of academic presses that have, with a focus on the most recent news about Johns Hopkins University Press.

Many authors are outraged at these deals, and some are suing or writing open letters. Others are just confused: can their publisher do this? Should they? Should they opt out? Will they get paid? The short answer is, because it’s an entirely new area, there’s no answer. But here’s my opinion:

Publishers aren’t being evil by making these deals. It’s a brand new area to them, and one could say it’s all putting them in awkward position. And these deals can be lucrative.

Publishers who do make deals should give authors included in such deals the option to opt out.

Publishers should compensate the authors who do not opt out in line with their current subsidiary rights splits, if they exist (75/25, 50/50, etc.)

There are probably more risks to opting out than opting in. I think about it with Amazon as a parallel: many authors decry buying on Amazon, but few refuse to have their books sold by them. Ditto with very few refusing to have their book indexed by Google search (should they have such a choice). There is a risk of being shut out of research, conversations, etc. This does not mean you should not opt out!The money is always best at the beginning. Tha’s one thing we’ve learned during the digital age. And all the money may all go away entirely, given legal cases.

Companies that pirated the material for their LLMs did not, by definition, enter into contracts with publishers to request use of that material.Many seem to think “AI” is one big entity. It’s not. There are many private companies creating LLMs, each trained on different material. Publishers could license their books to more than one of these. So when people say “everything has already been pirated and stolen already” they are conflating one company (which might have pirated, as with LibGen data pirated by Meta that many read about in The Atlantic), with all AI companies. ChatGPT is run by Open AI; Claude is run by Anthropic, Gemini by Google, Grok by XAI, Llama by Meta, etc. As far as I understand, these licenses are not exclusive, so yes, publishers could do deals with multiple AI companies. And not all LLMs have the same material, because they all have different training sets.

Is this clearing anything up for folks? I hope so. But remember: I am not even touching the ongoing legal cases, or the question of fair use. If it’s decided that what these companies are doing is fair use, then all the rights and licenses and potential money could be off the table.

Want to read up and follow this more? I suggest Authors Alliance.

I am also not touching the debate over using AI to write books, or people in publishing using AI to produce books, or open letters asking publishers to not use any AI. I’ll say this though: I find calls to abstain from AI misguided, because AI is baked into so much of what we already use, and how search is already done, that it’s impossible to draw such lines. It can sound a bit like judging people for using spellcheck. Not to be a cop-out, but: it’s complicated. It’s just complicated. So we need nuanced takes, not blanket calls for prohibition.

A few other notes:

The web is a mess: it’s becoming increasingly hard to research (including this topic!) As Google’s AI (the only one I consciously use) gets better, I often find it easier and more reliable than search results. Consider this a statement about how crappy is search in general—on Google, on Amazon, on databases—rather than a plug for Google’s AI mode.

That I have found myself pulling the Google AI drop down menu more often of late is a real concern for any business or non-profit built upon website clicks. This could cause serious problems for independent news outlets, for instance. This is one reason, I think, why many are embracing newsletters. Makes sense. Now we need to disentangle the problems of Substack—which are real and to be attended to—with the fact that it is, right now, the best platform if you want new people to discover you newsletters and, by extension, your news outlet, say, which people aren’t clicking on because of Google AI or whatever.

I don’t find AI to be very useful for very much. Maybe some better results than Google search, and an alternative to wikipedia. Maybe some improvements in spreadsheets. It still seems like a solution in search of a problem.

if you have found errors in what I’ve written above, drop a comment! I’m trying to understand and explain all this as I learn, but I am not an expert.

I cannot tell you how much I appreciate the clarity and breadth of the information you share. Thanks so much.