Over the weekend, Trump fired the head of the US Copyright office. A few days earlier, Shirla Perlmutter had released a report about AI and fair use.

Seems like a good opportunity to continue my series on copyright in the United States, as well as the importance of stealing to not just American publishing, but the nation as well. Our old friend Mathew Carey shows up again.

An earlier newsletter on the origins of copyright law in the US.

An even earlier newsletter on how American publishing is based upon stealing books.

Let’s go back to 18th century America. Everyone was ripping off everyone else. There was a flourishing of new newspapers being established, and most contained journalism swiped from other newspapers. A Boston paper would reprint what had been published in a Philadelphia newspaper, Philadelphia a column from Virginia. Etc. And as I’ve written about before, books published in England (or Ireland or Scotland or France….) were fair game, too. A printer just needed to replicate the text and publish the book under their name. And they did, in great volume, distributing to eager American readers cheap versions of books under copyright in their native country, but not here.

I use “ripping off” and “stealing” and “piracy” here because it jazzes up the prose, but it’s just as important to realize that few were miffed—people did not consider their journalism —- or their books—to be property as some do today. And further, there was a strong sense that it was one’s patriotic duty to steal. Only by stealing could the citizenry be informed. Information wanted to be free (or cheap)! Americans wanted cheap information! An educated citizenry was a good and noble thing! Remember, few considered their writing to be property. So the first American public was one reared on (excuse me, I’m sorry) the LLMs of the Long Eighteenth Century.

The Stamp Act of 1765 spurred this movement even further, as colonists realized that native manufacturing would be important to their incipient revolution as well (hello tariffs and protectionism! Look how timely). They agreed to nonimportation pacts—no buying of British books, or anything produced by other countries—and started organizations to “buy American”. Most of materials used in the publishing trade were too expensive to recreate domestically—they still got their type and presses from England, mainly—but paper did start to be produced in quantity in America at this time.

So an intentional, ideological practice of stealing became codified: “America’s first major domestic publishing venture was a Bible with a false imprint attributing it to the king’s printer in London, and Boston booksellers were still falsifying London and Dublin imprints in the 1760s.”1

Publishers draped this practice with the flag of patriotism: a hunger for printed materials amongst the colonists needed to be met, and could only be so by “freely disseminating knowledge.”

The pirate publisher became a revolutionary figure, with Mathew Carey the most outspoken and famous one; he even had a duel with a British journal publisher who decried Careys reprinting. He lost, and a thigh injury sidelined him for 18 months.

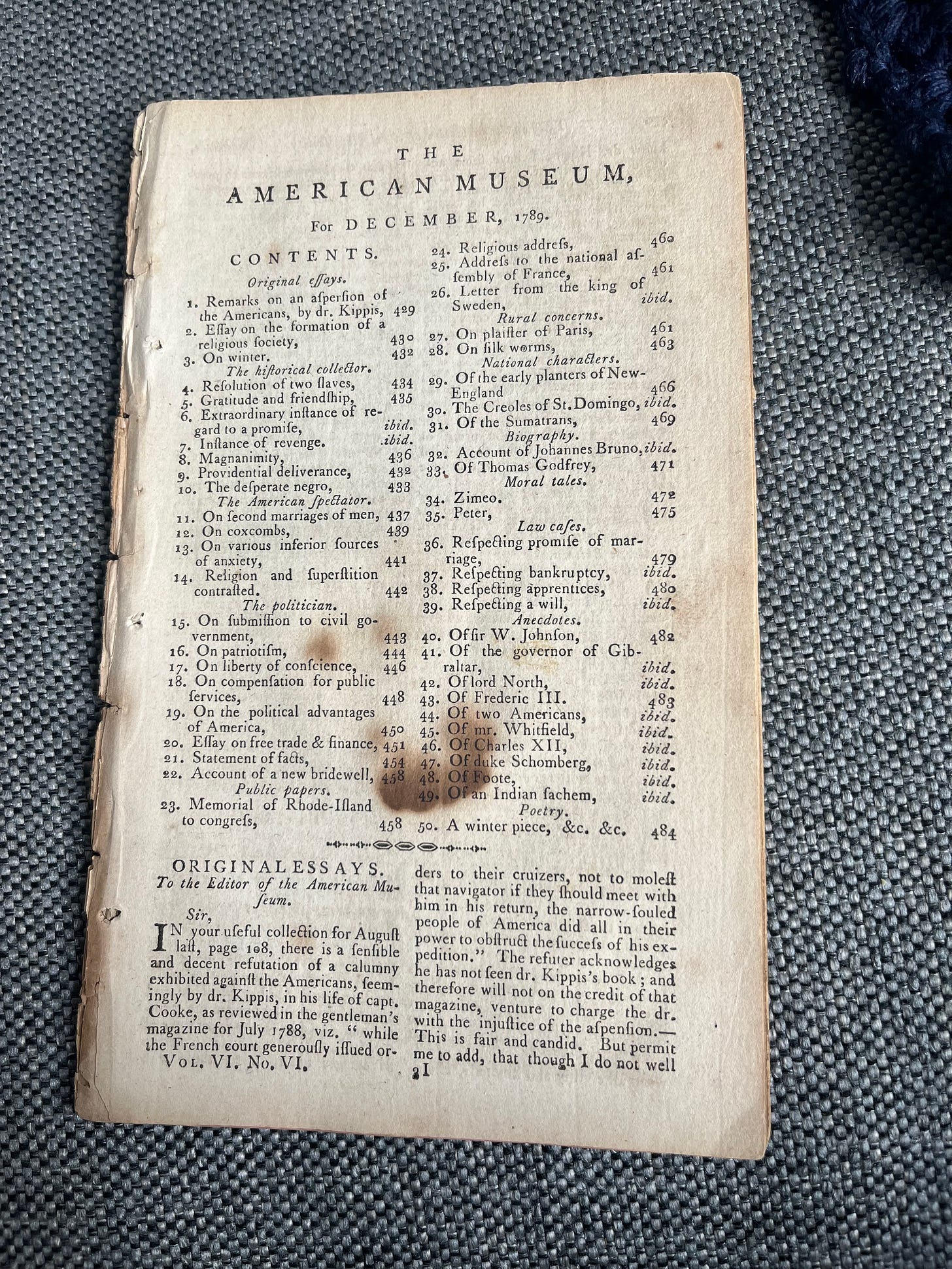

The first American magazine, started by Carey, called the American Museum, consciously reprinted as much as it could, publishing Common Sense and the Federalist Papers. George Washington blurbed it as “a more useful literary plan has never been undertaken in America.” As Johns puts is, “Carey and the American Museum became principal agents in developing a republican ideology of appropriating European knowledge while protecting domestic manufacturers.”

Congress asked Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton to study American manufacturing, and American Museum became a key organ for disseminating this protectionist agenda, which included tariffs. Publishers were told they should double down in reprinting. They were urged to use “the opportunity of publishing immediately, for the American demand, all books in every European language” (Johns 191), and to sell those books in plain, cheap editions that people could afford.

Pirating as much as possible, as quickly and economically as possible, was how American could make itself as a literate, informed nation. And by doing this, the early Americans who were at first printer, publisher, and bookseller in one, slowly transformed themselves into publishers as we think of them today, outsourcing the printing and retailing of their books to others who were creating of them new, standalone businesses.

And so it stood, for about another century, until the international copyright law was passed in 1891. Until then, American authors were protected under copyright for a term of 14 years, but only in America, and foreign authors had no protection. Mark Twain moved to Canada and became a resident so he could claim Canadian copyright of The Prince and the Pauper. British authors often worked with an American to have the American register copyright (and then send proceeds to the author). Charles Dickens’s famous American tour was spurred by his desire to see copyright extended to British works. But there wasn’t much impetus for American publishers and printers to pass such a copyright law, as they benefited from high tariffs, and they were in the sweet position of not having to pay royalties to foreign authors—something that, as we’ve seen, helped them establish themselves as a viable industry in the US, as well as an American ideology based upon the importance of disseminating as much knowledge as cheaply as possible.

When the international copyright act was finally passed in 1891, it included a “Manufacturing Clause” that required all books by foreigners be set domestically, using American type. So American publishers had to pay royalties to foreigners, but now all books had to be made in the USA (so it would have been illegal to do what many publishers do today: send books to China or other countries where printing is cheaper, to be produced and shipped back).

Twain wanted even more protection, and money of course, for authors, though, and we would spend years lobbying to increase the length of copyright. He is one of the main reasons American copyright now extends for decades beyond the author’s death.

—Two months until my book proposal course begins.

—Check out this lovely article that includes a discussion of Belt and a recent release in The New Yorker.

Research for this newsletter comes from Adrian John’s Piracy: The Intellectual Property Wars from Gutenberg to Gates.

An edition of this magazine I bought on eBay.

a college friend had a job with Dover. She was hired to look for interesting books out of copyright some of which they reprinted on excellent paper w/sewn signatures but paper covers. Several of these editions are on my shelves 60 years later without the awful paper rot of cheaper paperbacks. I worked 6 years in the book trade, in stores, and as a salesman calling on stores in NYC. This was the era in which ACE printed the Lord of the Rings in the US claiming the UK copyright was void. it was also the era of competing mass market "classics" for school adoption--how many different editions of David Copperfield, or a single Shakespeare play should shelf space be taken up with?

at the other end of the scale, I was often asked by retail customers for books which had gone OP. I began to believe that if a book were OP, copyright should default to the be void.such that any other publisher could reprint on condition of paying the industry standard royalty. I should point out another oddity from the 60s. Ace Doubles were two novellas printed as a single book. It is said that several "joint authors" compared their sales/royalties finding somehow they had not sold the same number of books.

Interesting history on publishing and piracy in America.