My book proposal course starts August 7. Plenty of space left. If you are interested and the fee presents a hurdle, email me at anne.trubek@gmail.com.

I am ruthlessly pro-history and rapidly anti-nostalgia. This puts me in the odd place of seeing a publishing-history-related tweet go viral and, instead of being happy to see my pet interest racking up numbers, finding my fingers getting itchy, eager to add context.

Said tweet

My first instinct after I read this was to say “but not the publisher of Louisa May Alcott!”

Alcott had to support her broke parents (her father, Bronson, was and is well-known, but incapable of making any money), so she moved to Boston to work as a teacher. What she wanted to do was write, and she published a few pieces, but they weren’t bringing in enough. In 1862, she moved in with her cousin, Annie Adams. Adams was a writer, and married to James T. Fields, of Ticknor and Fields.

Alcott asked Fields to read a story of hers (which would eventually be published in The Atlantic). Fields responded by telling her to “stick to your teaching; you can’t write.” He gave her $40 to support a school she had just opened, instead, and said she could pay him back when she struck gold. (Later, after another publisher gave her a contract, and she sold enough copies of Little Women to make her and her family well-off, she paid Fields back, writing, “I wish to fulfill my part of the bargain, & herewith repay my debt with many thanks.”)

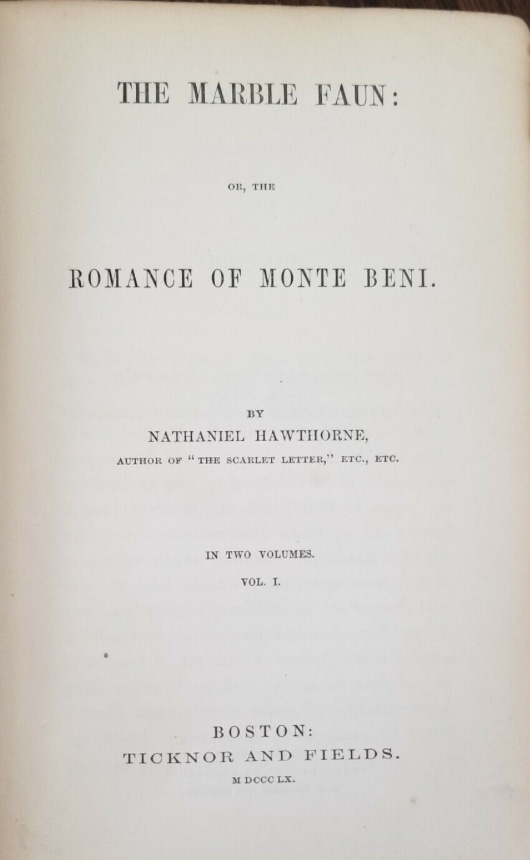

In 1863, Fields gave Nathanial Hawthorne, whose Scarlet Letter the firm had published, an advance on a book that didn’t exist, gave it a title, and announced it to the public. Hawthorne never finished the book Fields thrust upon him, and Fields would throw the partial manuscript into Hawthorne’s casket during his funeral. Hawthorne’s widow, Sophia Peabody, later threatened to sue the firm for not paying royalties it had promised.

It was not the first time death and Hawthorne came for the firm. In 1864, Hawthorne was ill (perhaps depressed) and Ticknor took him on a trip south to Philadelphia to help restore his health. The night they arrived, Hawthorne felt sicker and was cold; Ticknor gave him his coat, to keep him warm. Ticknor woke up with a cold, and by that evening, Ticknor was dead.1

Alcott gave one a sick burn and Hawthorne killed the other. Ticknor & Fields were more men of letters. Amusing anecdotes about the house and its owners are buried in the archives, which are so slim that I read a M.A. thesis from 1942 complaining about how thin are the archives, as well as all American publishers, a fact that I continue to exclaim in astonishment to friends (who strangely find it less incredibly interesting!) over drinks.

This scholar was also stymied in her research by another fascinating historical fact (God bless the internet, which allowed this scan to be googlable, and also access to copyright information even during wars, or pandemics):

So what happened to Ticknor & Fields? To the offices on top of the Chipotle? What happens to all publishers, apparently: they went broke. They did in fact shepherd the “flowering of New England” into being, publishing many well-known (then) and oft-taught (now) Transcendentalists, and creating what is called the flowering of New England and the American literary renaissance. But it grew to cost more money to keep those now famous authors. Their overhead got bigger. They invested—they bought The Atlantic and other magazines. They signed up new authors, including Charles Chesnut and Mark Twain. But Ticknor—the one who died next to Hawthorne—was the business minded one of the two, and Fields couldn’t make the numbers work on his own (too bad he passed on Alcott, huh). He abandoned ship (aka “retired to work on his writing”) in 1871. James Osgood took over, but it was already a losing proposition. Osgood sold off a lot of what the company had just bought, and moved the firm out of the twitter-famous building to cheaper digs. In 1872, the Great Boston Fire turned much of the city’s publishing industry to ashes. Huge losses were reported. Then, authors started leaving, including Longfellow, who had made enough money selling poems (poems!) to quit his job at Harvard (Harvard!) to write full time.

Next comes the part of the story becoming oh so familiar, the litany of mergers and acquisitions. Osgood merged with another publisher, Hurt & Houghton. That company became Houghton Mifflin. That company became Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. That company went through a dizzying numbers of mergers, acquisitions, and restructuring. And recently, in 2021, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, along with the assets created back in the day by Ticknor & Fields, became a subsidiary of HarperCollins.

The offices are gone, the company is gone, and on a walking tour all you can see is brick. But it’s easy to find the work Ticknor & Field did, the wares they sold, at any bookstore. It’s even easy to find the originals: eBay is filled examples of their trade (slash art slash craft). The night I read that tweet, I spent hours sleuthing, and bought myself some Ticknor & Fields first editions. They cost about twenty bucks each.

(Well, this is as those stories goes. A few anecdotes about those anecdotes: Annie Adams would later leave James T. Fields and live the rest of her life with Sarah Orne Jewett. Scholars love to discuss the possible relationship between Melville and Hawthorne, who was completely devastated by the death of Fields,

This is good history! I find myself interested in learning more about Fields, about publishers, about whether or not that Chipotle would cheat me out of salad greens like the ones around here...

Thanks! To chime in on the historical, I love how Thoreau sent a Scarlet Oak leaf to Ticknor & Fields--"the smallest one in my collection"--to insert "a faithful outline engraving of the leaf bristles & all" about page 57 of his book, above the words: "'The original of the leaf on the opposite page was picked from such a pile.'" Their relationship must have encouraged Thoreau's famed commitment to his books' material design. So beats the images on Chipotle menus ...