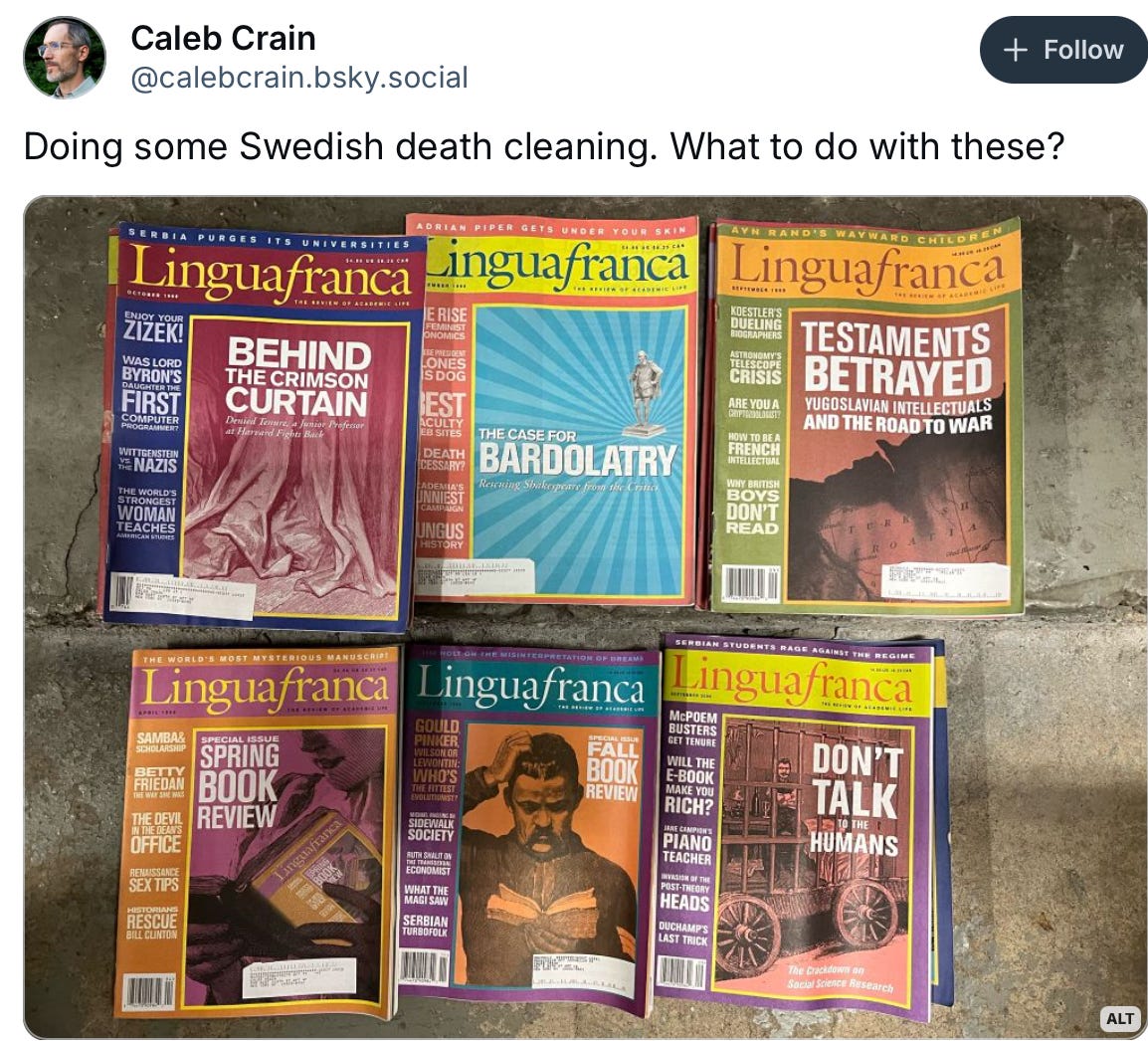

The fabulous writer Caleb Crain led me down a rabbit hole when he posted this:

Nostalgia for Lingua Franca, the best “magazine of ideas” of the last half century (I say, rounding down, being too lazy to consider if there might have been a better one over the past century) is common amongst my cohort. “Ah, Lingua Franca! It was the best! So sad it didn't last longer!” At least twice during the heyday of ‘academic-esque twitter’ (at least for me) a group of us tried to revive it. I think I even have a Google doc somewhere.

Lingua Franca was truly exceptional, of its moment, and extraordinarily influential (to me and many others; reading it inspired me to take my first steps away from scholarly prose to journalism and nonfiction,). It had 15,000-20,000 subscribers (!!!!!). Those who wrote for it still continue to be some of my favorite writers, including Peter Beinart, Ruth Shalit, Jennifer Schuessler, Laura Secor, Daniel Mendelsohn, Clive Thompson, and of course Crain (and so many others; truly a who’s who list). It closed suddenly and mysteriously in 2001. (There’s a story yet to tell).

After I saw Caleb’s post, I tried to remember if I wrote for them; I know I had wanted to, but this was a bit before I started doing a lot of freelancing. So I googled. Nothing came up with my name and the magazine’s name, so then I went to find the archives.

The first thing I found was a mirror site done by Aaron Swarz in 2005. Whoa. Another bit of intellectual and internet history right there. This led me to an archive, but a very partial one, only from the last few years of its run. (Still, look at these squibs, from those years!)

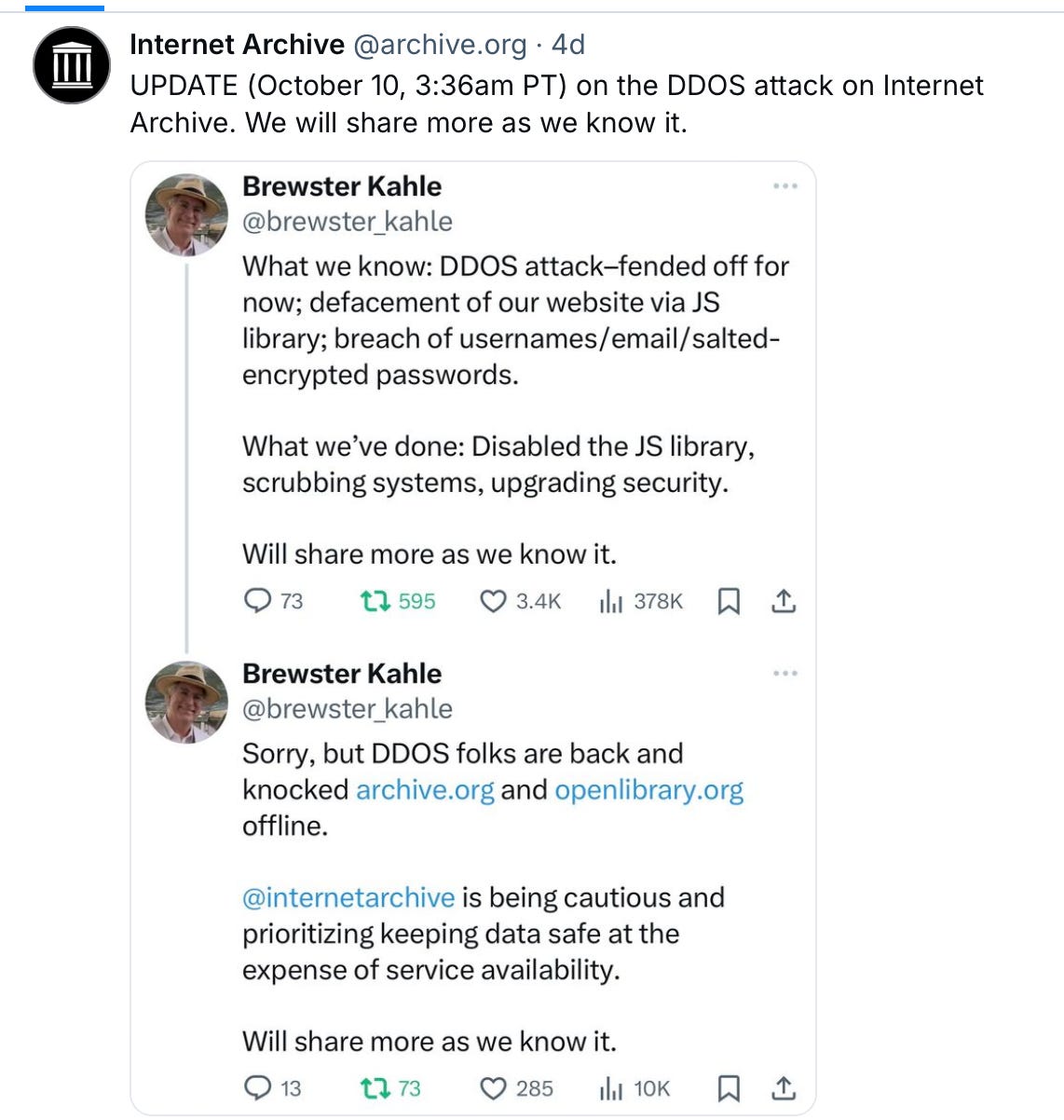

My next hit was to a “best of” book published in 2002, and the top link to the book was from the Internet Archive. That’s a reliable (if controversial) way to find what has otherwise been lost by the internet, right? Well, it’s been hacked.

At this point, I had forgotten my ego search to see if I had written for them—a memory hole of my own—and was instead focused on the magazine’s seeming disappearance from the Internet.

Look, preserving the writing of the past has always been much more difficult than many assume—and get self-righteous about, as with outrage over the normal and necessary work of library weeding. Books burn in both myth and reality; floods soak; ink fades. (When I was doing a lot of interviews for my handwriting book, people kept saying paper was better at preserving the writing of the past than computers, an argument that never made sense to me). There are numerous experts and new fields dedicated to web archiving. But Lingua Franca was born in an energetic and fertile moment for both humanities in the academy and longform journalism, and both these fields have since been gutted. And now “the internet” seems to be gutted as well. It is increasingly difficult to search, due to AI and the enshittification of Google and other tech platforms.

People often use “perfect storm” incorrectly, to describe a good thing, so to borrow that mistake: Lingua Franca was a product of a perfect (good) storm of intellectual energy and engagement, and now it is victim of a (correctly used bad) perfect storm of neglect and deterioration. Poignant!

I doubt even the most entrepreneurial and brilliant would attempt to revive Lingua Franca now (even worse, such an effort could end up being as disturbing as the QAnon revival of George, another magazine of this period). It would be lovely if someone did take on the quieter work of putting its full archives on the internet, and I’m sure some fine librarians have preserved a full run of the print edition. The writing is not gone, or lost, but it’s much harder to find, literally and metaphorically.

I briefly toyed with pitching a longform piece on the rise and digital loss of Lingua Franca, a case study of the gutting of the humanities and nonacademic venues for writing about ideas over the past few decades, framed by the deterioration of the internet in this one, but then I tried to think about who I might pitch to, wandered in my mind through the now defunct digital outlets of the past that might have been interested, and then tossed this idea, like so much else of our past, aside. Maybe it’d be better as a book.

There are four spots left in my book proposal course starting November 11. Sign on up and join the gang!

I sure hope he donates his copies, because at first scan, there's a ton of gaps in university library collections! The only paid database has issues for Feb-Nov 2001, and links to an obsolete domain name.

Re paper vs digital -- both is good. Scanning and correcting/cataloging scans is expensive. Paper is cheaper to preserve and rehome than digital media and is less likely to become unreadable. But yes indeed, the cloud can survive the floods and burnings and students with scissors.

I'd read that long-form essay / book.