HarperCollins workers are on strike. I’ve been keeping up with this news through the twitter feed of the strikers (@hcpunion), and reading substacks, including

, which sent out a great guest post by striking employee Rachel Kambury. It has lasted 19 days, their longest ever.I support this strike—said even though I admittedly know less about it than I should (and plan to catch myself up once my workload slows down/the World Cup ends). A publisher on strike causes complicated decisions for authors under contract (how should they support the strike, or not?), as well as agents. Perhaps even for reviewers and booksellers. Should a big name author who has a book coming out with HarperCollins during this strike refuse to promote it? Should agents refuse to send submissions to editors during the strike? Trying to answer those questions is a good way to understand the complexities of publishing. What relationship—legally, ethically, morally, politically— does an author under contract have with a publisher? An agent? A bookseller?

I was working through my thoughts about this a few weeks ago while coincidentally reading a book about the history of Harper & Brothers, the same Harper as in HarperCollins. Let’s scroll backwards:

Today, HarperCollins is a subsidiary of NewsCorp, and thus owned by Rupert Murdoch. It has been since 1990, when Murdoch bought Harper & Row. NewsCorp also bought Collins, and merged them.

Harper & Row lasted from 1962-1990. During that period, the company bought Lippincott and Zondervan.

Harper & Brothers was born in 1833 and lasted until 1962, when it merged with Row, Peterson, and Company to become Harper & Row.

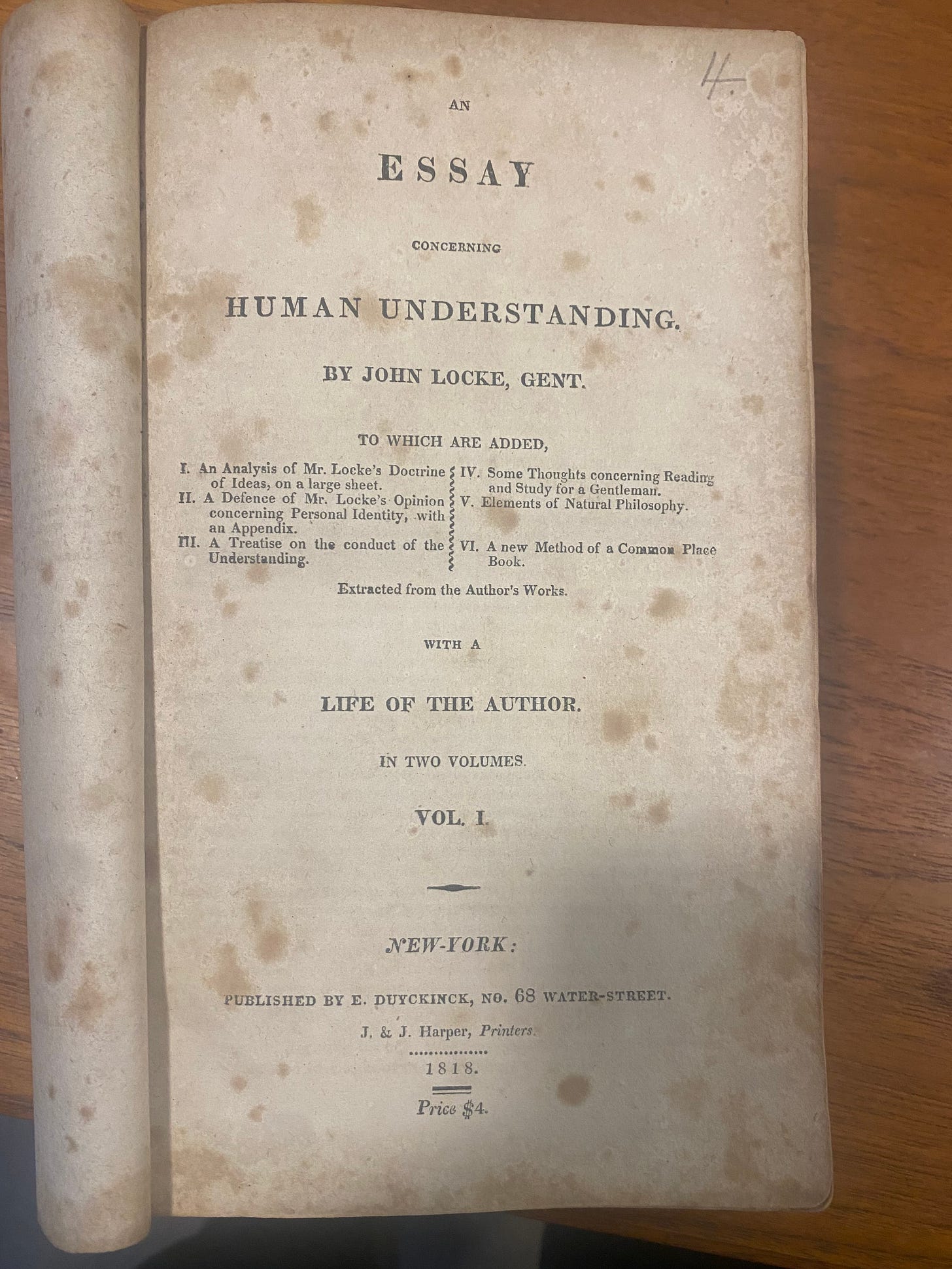

And even before the birth of that historic of American publishers, it was J & J Harper, from 1817-1833, when two brothers, James and John, then printers, set up shop in New York City to publish books as well. There were 33 booksellers in New York at the time, and the Harpers wanted to provide them with books. But first they needed orders. It took awhile, but they did get one order from a bookseller for two thousand copies of Seneca’s Morals. When the job was done, they showed their work to others, but still didn’t receive commissions. So they decided to just come up with a book to print on their own, without an order from a seller. They chose John Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. They made proofs, showed it to some sellers, and solicited advance orders. They promised sellers credit on the title page if they ordered copies. It worked. They received advance orders, and published the book in 1818. It is the first ‘real’ publication by J&J Harper, aka HarperCollins.

I have a mild addiction to book collecting—-scouting, really. I like to find books of value and then flip them. So I know how to go down internet rabbit holes. So one night a few weeks ago I dug, and dug, and I am now the proud owner of a copy of that first Harper publication, purchased for $35 from someone online. It was listed as “Antique Book; Very Old” or something like that, but with keywords and zooming I was able to find the information I was looking for.

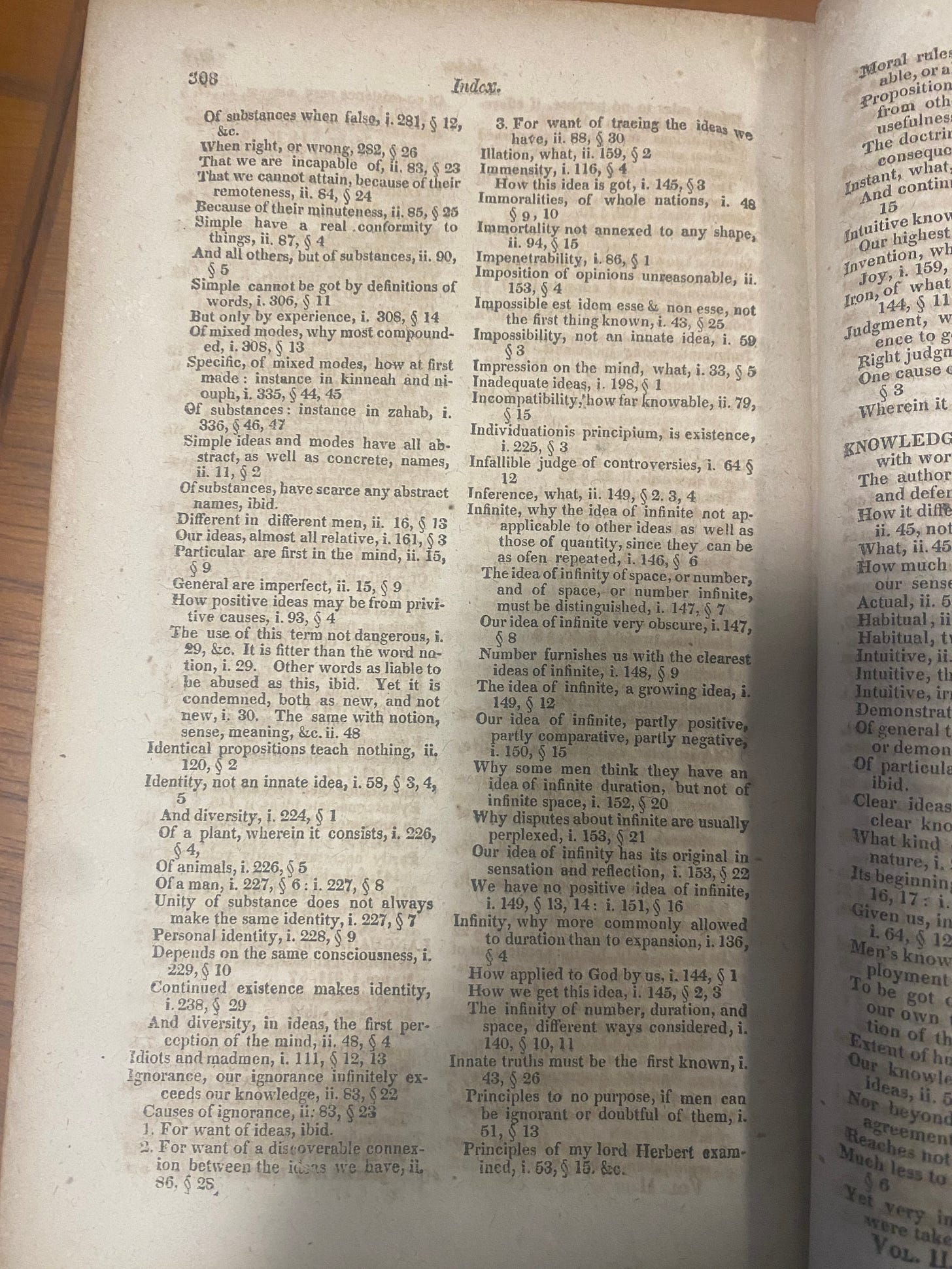

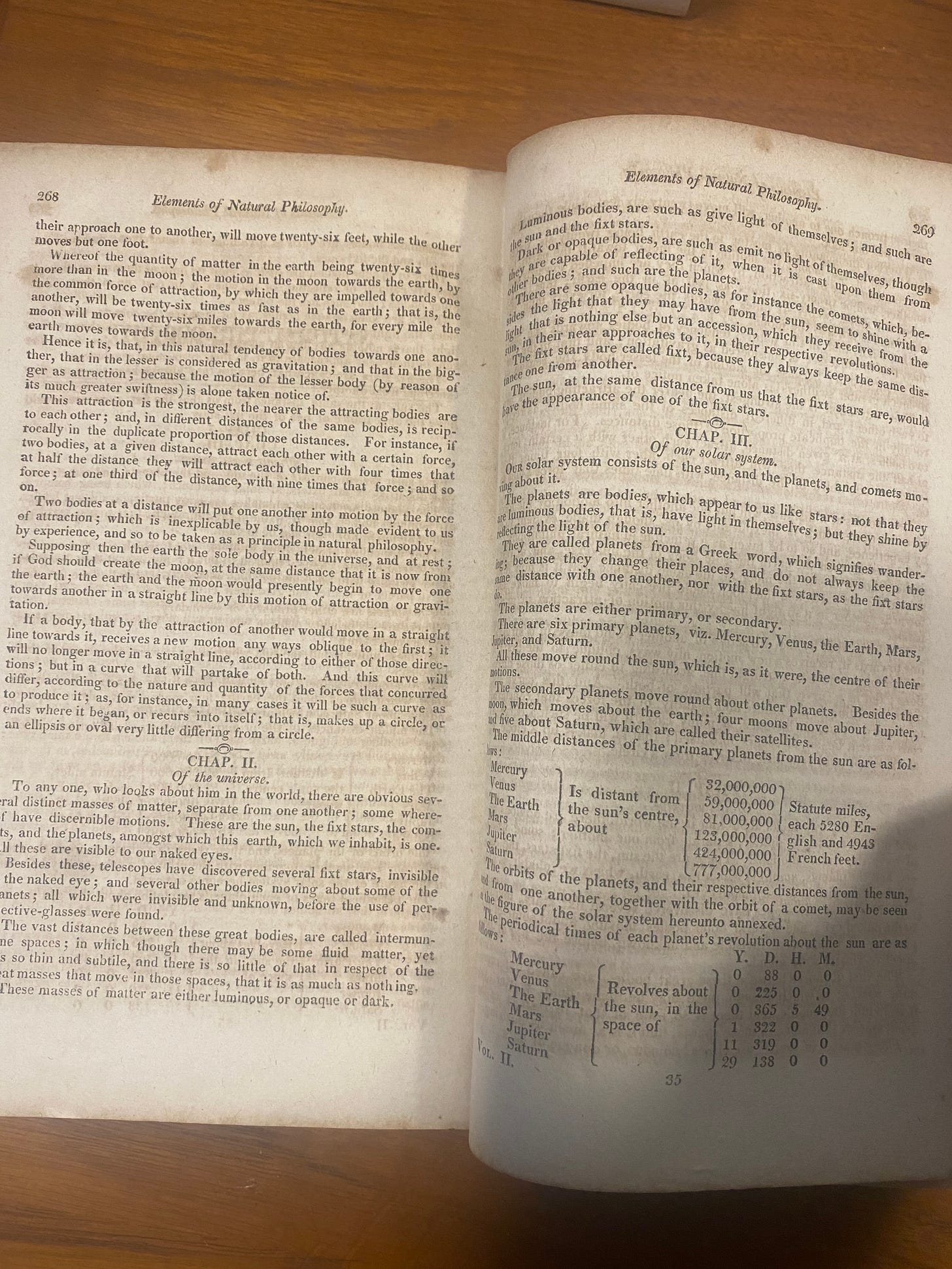

Imagine setting the type for that index. Imagine any of it—the labor involved in choosing letters from the cases, putting them in upside down and backwards into the compositor’s stick, making plates, pulling paper through presses. The work was done by James and John, as well as their little brothers Wesley, then 16, with the wonderful job title of printer’s devil, and Fletcher, just 11, on a school vacation.

The labor of book making, and well as selling, is still difficult and complicated. Those who do it deserve equitable compensation and treatment. While they are still on the picket line you can support the heirs of Wesley and Fletcher by donating to the HarperCollins Union Solidarity Fund.

I’m teaching an online class in January to help those interested in writing non-fiction books with ideas and proposals. Check it out! Tell your friends!

According to Google, $4 in 1818 is $94.61 today!

My smooth baby brain, once again failing to compute that companies change all the time: there was a Harper & Row???

Congratulations on the find! It’s amazing what kind of history can be held within a single object, and also how cheap that history is sometimes.

I hope the striking workers win. They deserve it (and let’s be honest, they probably deserve *much* more than what they’re actually asking for) and the industry as a whole desperately needs this win. We cannot afford to have another generation of workers scrounging for pennies. The longer publishers are allowed to mistreat people, the harder it’ll be to fix later.

And I know you’re deeply familiar with this being a native of the Rust Belt but *points at the world* so many things are in crisis now because they didn’t get handled 10/20/40 years ago. It’s about time something actually got fixed!