Like many others in publishing, I’ve spent a lot of time following the DOJ vs PRH trial, mainly through John Maher’s extraordinary live-tweeting. I’ve found myself rather overwhelmed by the evidence and testimony. I didn’t think I would much of interest to me, as a farily new independent press publisher; I thought a trial between a multinational corporation and the federal government would involve incomprehensible mergers and acquisitions laws and business jargon. Instead, the talk has hewed surprisingly close to the stuff I chat about in my day job: advances, or how much of our money we should to risk now for a manuscript that will we will make into a book a few years later; print runs, or predicting how many copies a book will sell; marketing, or how much we should spend for a particular title; P&Ls, or if, when we look at the numbers a year after publication, they match our old bets; sale, or whether we should blame ourselves or the vagaries of the market if sales don’t meet expectations, or if we can give ourselves any credit for the ones that surpass them.

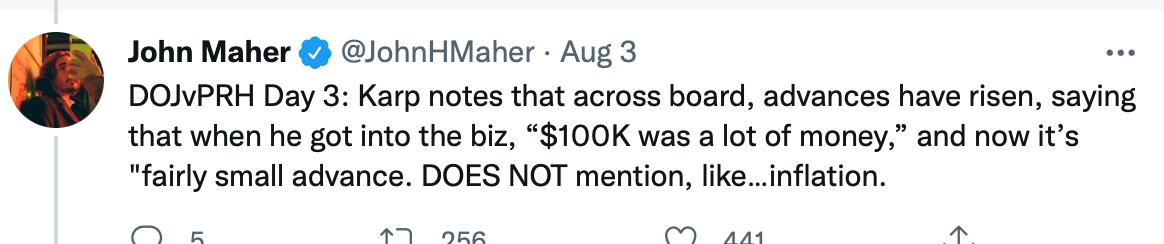

What I have learned is that the aspects of publishing I find flummoxing and impossible to predict are, well, actually flummoxing and impossible to predict for everyone, including the biggest and highest in the profession:

I mean all you can do is laugh, right? All this time I wasn’t sure I knew what I was doing and it turns out…I have had lots of extremely well-compensated company all along.

Of course, some of the conversation does involve discussions in scale and size unimaginable to me (as well as to the vast majority of authors and publishers):

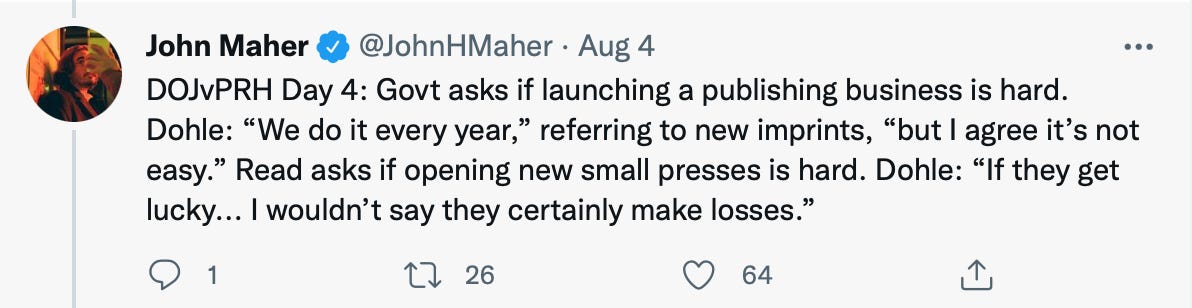

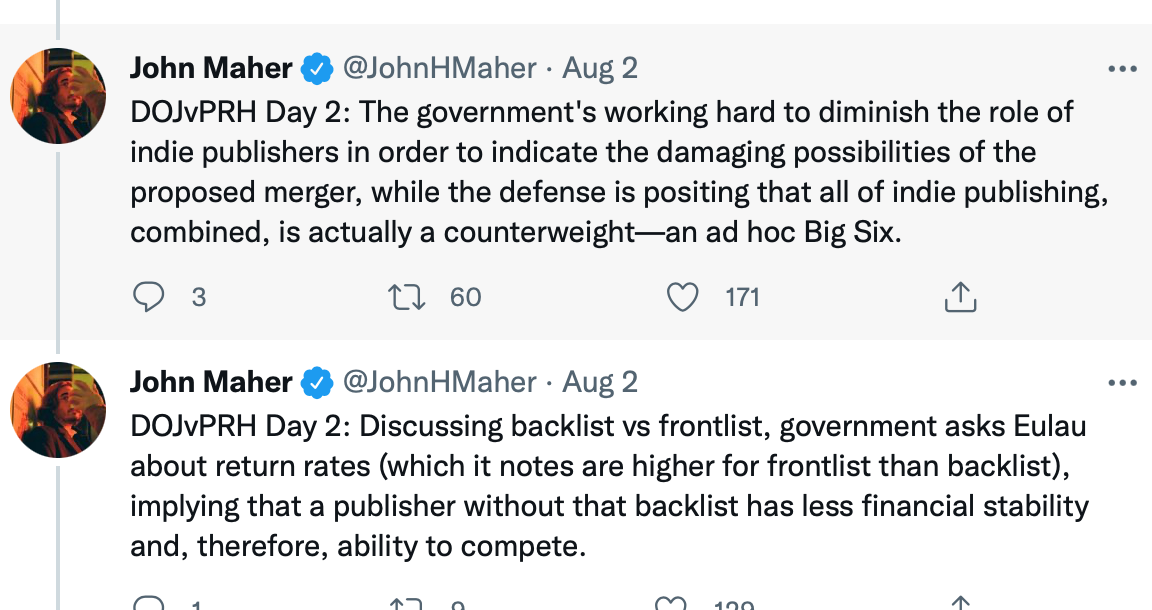

Indie presses get more air time than I would have predicted, as does the importance of a backlist: the longer you are in business, and the larger your backlist, the more financially stable you are, the more advantage you have other other newer, smaller presses:

And I definitely sat up straight during this exchange

In addition to Maher, with his yeoman job on the site, others have weighed in on the events thus far. Here are three I found very smart: I agree with everything in all of these and they all write up the proceedings well and amusingly as well:

Jane Friedman’s take in the Hot Sheet

John Warner, “Stop the Merger”

Kenneth Whyte “The Biggest Story in Books”

Me, I’m mainly still staring slack-jawed at the whole spectacle, rather than analyzing or coming up with take: I’m mesmerized by the executives throwing up their hands saying “it’s just incomprehensible casino magic!” as well as delighted by the judge and lawyers asking questions as they desperately try to understand what the fuck this business is, anyway.

But mainly what I think about is the worth of what’s to come. Publishing, it seems to me, is founded on two impossible abstractions: one, the future, and two, and literary value.

The future is always the present in publishing-and it is what the lawyers keep asking the CEOs about. After all, “advance” is a nominalization, and it’s easy to forget it should be a verb. Nothing I did in my job on August 8, 2022 is about August 8, 2022: I’m a futurist as much as the next tech guy. Time also has to move forward and then reverse on itself, as, as the trial has also made clear, the backlist is so central to the business. Publishers—from little me to Big Jonathan Karp—must consider how a book we might publish in 2025 would sell in 2030. The bigger and better backlist, the more stable and profitable a house will be (Hachette said 30% of their $300 million revenue is backlist sales. To create a backlist like that—one that will sustain a company—takes decades. It takes many future years to create a past. One is always doing precisely what meditation gurus and mindfulness apps tell you never to do: think about what you have no idea about, what has not yet happened.

Literary value is the second foundation— and by this I don’t just mean literature, but the value of any text. Literary value—*very importantly*— is not the same as monetary value. And yet monetary value is best gained via literary value—because it is those books that create the backlist, as opposed to the momentary dopamine hit of the instant bestseller that only sells for two weeks. It is in that crease—that crease between “value” vis a vis art and culture, and “value” vis a vis business, capital, money, dollars, profits, revenue, assets—that a publisher must smooth. It is an impossible crease, one that creates gutters as you to stitch together the two values like case blocks into leather bindings, preparing books not yet made meant for readers who don’t yet exist.

Notes from a Small Press is the newsletter by Anne Trubek, the founder and owner of Belt Publishing. Subscribe to receive every post. Oh and don’t forget to grab a copy of So You Want to Publish a Book?, the book based on this newsletter that other people say good things about.

One of my favorite things is reading what you, Jane Friedman and Eric Hoel have to say about the big-publishing world and then being glad I just do my thing here on Substack. :)