I am over the moon seeing all the reviews, takes, and “book adjacent essays” surrounding Dan Sinykin’s Big Fiction, officially out today. I must now add that I’ve read some but not most of the book (do you know how you avoid certain things because they are “too close” to what you are supposed to be working on? That’s me, with this book. I’ll get to it when the noise in my head settles down). But I’ve been reading Dan’s essays about the book’s topic, and I’ve been thinking about his one about literary fiction, in particular, his discussion of the category “literary fiction.” I’m using his piece as a jumping off point to talk about BISACs, the most important acronym in publishing you may not have heard of.

Dan discusses the use of “literary fiction” to describe contemporary novels that few would describe as literary— “You can now find The Mister, an erotic thriller by Fifty Shades of Grey author E.L. James, on Amazon’s best-selling literary fiction list” and “The international mega-bestseller Where the Crawdads Sing is listed on Amazon as literary fiction. So is the immensely popular, self-published Love Me Today: A Single Dad, Small Town Romance.”

But you would not find, say, Politics & Prose or Pilsen Community Books or any other independent bookstore categorizing those books as literary fiction. Nor would the publisher have used it as their main generic description for those books. Because those places use BISACs.

More on BISACs in a minute, but first: Amazon. Amazon’s categories are only applicable to Amazon. No one else uses them, and they are wildly inaccurate and idiosyncratic. (We’ve had Belt books becomes “#1 Bestseller in Sociology of Knowledge” for no reason we can discern). Amazon categories are based primarily on keywords—the terms consumers use to search for books. Publishers also add keywords to their metadata, to help their books be found by those consumers. (This causes publishers—I can’t imagine Belt is alone—to put in keywords that we think will be popular, even if they don’t exactly describe the book). Think of Amazon categories as basically SEO. Publishers also add BISACs, and those are more important in many if not all respects than the Amazon-demanded keywords.

BISAC codes, are how publishers, booksellers, some libraries, distributors categorize books. There are thousands of them And they matter, very much, to promoting, distributing, and selling books.

BISAC stands for Book Industry Study Group. It was founded in the 1976 to help sort the mess of books out there. Read about their since-expanded mission here. BISACs are not, unhelpfully, the same as the Dewey Decimal System of Library of Congress classifications, but within publishing they are the most important system.

Here is the list of main subject areas. Click on any of those to be overwhelmed by the subcategories. And even though it seems, as you click about, that there is no end to the categories, I still find myself flummoxed by some areas which seem thin to me. For example, Social Science is one subject area. Just one!

Novels appear in only one main subject heading, Fiction. And you can find Literary Fiction there, in between LGBTQ+/Transgender and LitRPG:

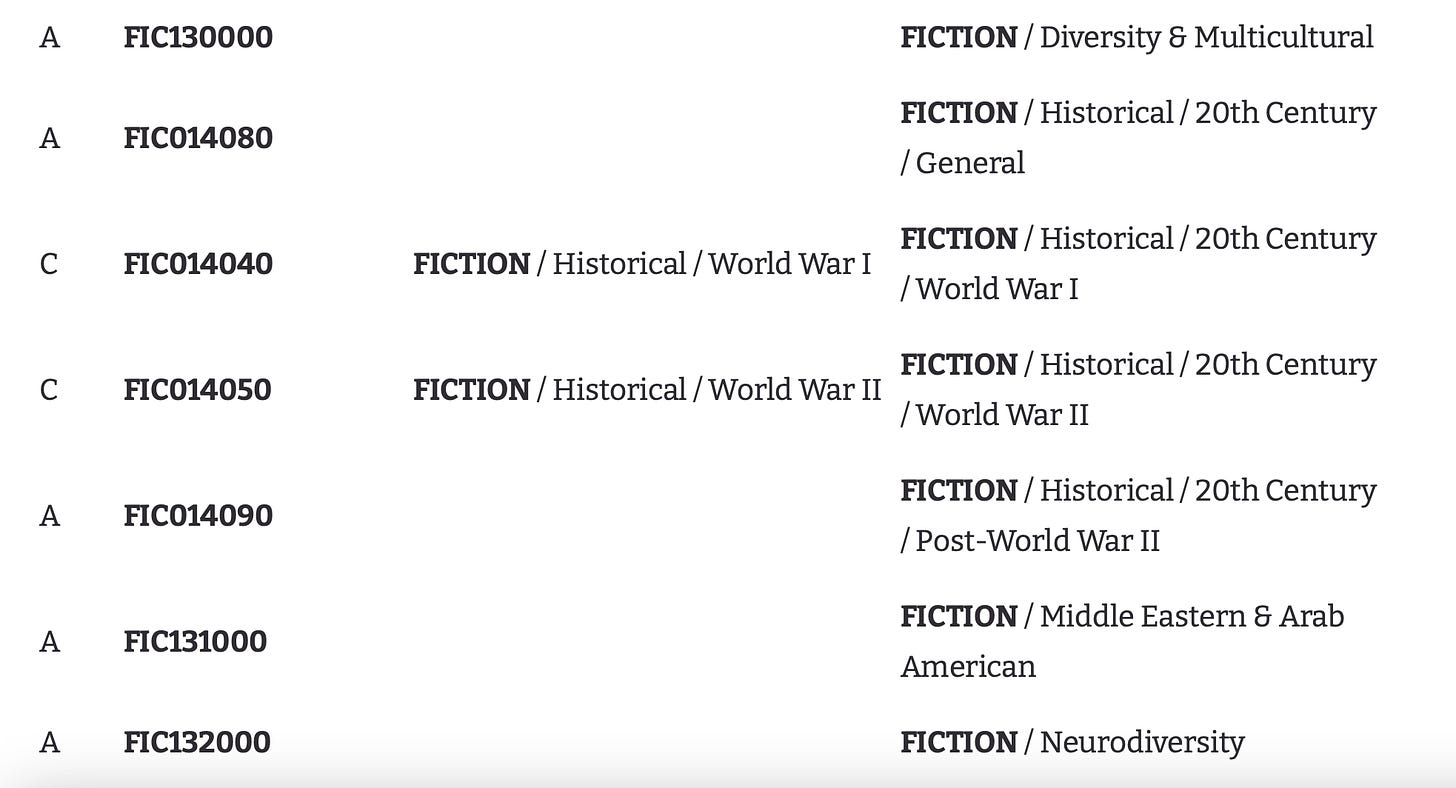

BISACs are updated annually, and I have long wanted to do a project that analyzes the new and discarded codes (calling my digital humanities friends!). In 2022, the following subcategories were changed in fiction (C indicates a change; A indicates addition):

And this category was added as well:

BISACs are often the first thing sales reps ask me about during pre-sales calls (“We’re seeing an uptick of interest in the “Literary Collections/Subjects and Themes/Animals and Nature” category—maybe make it your main BISAC?” ) (Best practice with our distributor is to include three BISACs per title: one main and two secondary). We have one title for Spring ‘24 for which there is no good BISAC, because it’s playing with form and genre, and so I let the reps know I was fine with not having an exact BISAC in the metadata. We will see. Have any of our previous titles been harder to find because we chose the ‘wrong’ main BISAC? Definitely possible.

I was thinking this morning, on my walk to the coffee shop (where I am now sitting), that for my book proposal course starting November 6 I might ask participants to pick their main BISAC for their book on day one, as an exercise. Might be interesting?

For more on BISACs and Amazon categories, I found this comprehensive. If anyone know of any studies done on the rise and fall of BISAC categories over the past few decades, I’d love to see! And if you are new to BISACs, an hour spent skimming all the categories would be an hour well spent.

I am so glad you wrote about this, because at first glance (I have not read Sinykin's book yet), it seems he might be making arguments about literary fiction today based on BISAC codes or Amazon categories—which is of course problematic because these are not assigned in a disciplined or consistent way by either publishers or authors, as your article shows.

One thing I will never forget is hearing someone at BookExpo discuss BISAC codes/categorization, saying that publishers very often choose some big umbrella category for their fiction rather than drilling down and being accurate/specific—and how this is a huge mistake for discoverability and sales. (Why aren't publishers better at doing this? I have no idea, maybe it's the assistants and interns who are assigning BISACs. And of course Amazon will do what it wants regardless.)

Sinykin seems to argue (in that Nation article, at least) that there is no a meaningful divide today between literary fiction and other fiction—he says it's "anachronistic" to speak of differences. Try telling that to MFA program graduates, AWP attendees, or any genre novelist. Or New Yorker critic Paruh Sehgal, who wrote about this partly in 2021, about Amazon changing the novel and the heightened anxiety of ... literary novelists.

This issue is the reason I'm on substack. I got fed up of reading through piles of landfill so-called literary fiction promoted in the mainstream press, only to find genuinely literary qualities in about a tenth of them.

True literary fiction, true literature, does still exist. It's out there. Never Was by H. Gareth Gavin is my favourite discovery in many years. But I have only found that book and equivalents by ploughing through the industry's output in a far more methodical, structured way.