Publishing is awash in cool terms. Many bear the history of now archaic print-making processes, such as "upper case" and "lower case", which refer to where individual letter types were stored. Some have less fun etymologies, but can make you feel all in-the-know and insidery. Below are a few.*

Signature. My favorite! A signature refers to a group of pages, printed on both sides, that a printer will print, fold, cut, and bind. Imagine a giant piece of paper, printed with 8 pages of a book on one side, and another eight on the other. The printer will fold this paper a bunch of times (and in a certain order!), then cut and then trim it to the size of of the book (that is, the number of inches wide and across for each page ,or "trim size." ), creating groups of pages they will then gather and bind.The number of pages in a signature varies; common signatures for common trim sizes are 8 or 16 pages.

This cool but pretty niche printer term is very important to my daily life as the keeper-in-mind-of-the-cash-flow because signatures and money are closely bound. When we are tweaking the final elements of a book, getting it ready to send to the printer, a question that hovers is often, "what's the nearest signature?" A book could either be, say, 288 pages or 304 pages (if the signature is 16 pages). It cannot be 289 pages, or 301 pages, because it must be as long as the last signature, a number divisible by 16. And since paper is expensive, a 304 page book costs more than a 288 page one to print.

Trim Size: Mentioned above. This refers to the size of the book. Go to your bookshelves and notice the variety of heights and widths. Some trim sizes are fairly standard, and will cost you less to print. Lesser-used ones will require more specialized equipment, paper, etc. from the printer, and will be more expensive. Choose your trim size wisely! Trim size is an obvious yet often strangely overlooked step in creating a a print-and-paper book out of pixels on a laptop.

Colophon: Okay maybe I like this one even more than signature. It's the penguin, the little house, the belt

A colophon is the logo or brand of a publishing house; here's a great story on the history of some colophons. (Did you know the little house was where Candide lives?) Colophon also refers to information about the printing of the book, usually in the back of the text, and mainly used in printings' earlier days. Colophons continue today, though: you know those weird "A Note About the Text" pages that are sometimes in the back? That tell you which font was used? Those are colophons too.

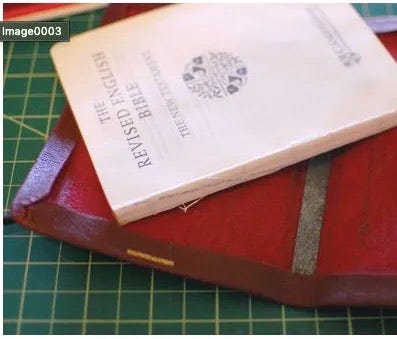

Strip and Bind. I have never used this one at work, but it's probably the best one (?) to work into cocktail party chatter (?!) Strip and bind refers to the practice of removing the interior pages of a book from its hardcover shell--leaving just the 'text block' (see picture)-- and then rebinding it to a new soft or paperback cover. Sadly, this exciting terms is usually only used in depressing circumstances: the publisher, having printed more hardcover copies than she can sell, has decided to convert some of the excess inventory into paperbacks.

ARCs and Galleys: There are long and short definitions of these terms. The long one would explain the difference between them. The short one -- this one -- will tell you they are interchangeable. ARC stands for Advance Reading Copy, and galley is a cooler term that contains history: printers used to place type into metal trays and run off a few copies that would then be proofed by editors. Then the printer would rearrange the letters and type in the tray upon receiving edits and re-set the final version.

Both terms are frequently used today, and interchangeably, to refer to pre-publicaiton versions of books. These are sent to book reviewers, media, booksellers, and anyone who warrants a peek at the book before pub date (or publication date). ARCs and galleys are often made before a final proofreading pass, and might lack footnotes, maps, or other elements that the final copy (or the version that will go on sale) will include. They lack barcodes or prices, and are not made for retail sale. They can be used as markers of prestige--read one on the subway to show how much of an insider you are! And they can be misused, as in this recent case, which still irks me. Never publish or publicly discuss material found in a galley until pub date, kids! Also, never, ever sell a galley--I'm talking to you, people who list them as third party sellers on Amazon! When you do, you take away not one but two sales from the publisher.

intermission for those who traffic in ARCs/galleys already: interested in an ARC or galley of a forthcoming Belt title? If you have access to Edelweiss, you will find some delectable forthcoming books there. We have print copies as well upon request ;)

Escalator Clause: Publishing contracts will spell out the royalties authors will receive upon sales. Some include an "escalator clause" to give the author more money as more books are sold. For instance: a royalty rate might be "7.5% on the first 5,000 books sold; 10% on 5,001-15,000 copies; 15% thereafter."

Print Run: The number of copies of a book you order from the printer, usually referring to the initial print run, or the wild guess you make months before a title publishes about how many books will sell.

Deciding on the initial print run is an art at which I suck: I have had to order a second printing, or second print run, of a title before publication date, based on initial orders, and I have a wall of books that I guessed wrong in the other direction. Publishers base their guesses in part on the number of books that have been pre-ordered. This is one reason pre-orders are important, but they can also skew things: an author might be able to convince 300 of her very savvy friends to pre-order to make the numbers look good, only to find out that there are not many more than 300 readers of her book after publication date. Another author might not be so keyed into the pre-order mantra, only to find that actual strangers find and adore the book a month after publication date, causing the publisher to scramble back to the printer, and stat. Other indicators of how many copies of a book will sell: the reputation of the author, the timeliness of the topic, pre-publication reviews, and tarot card readings.

Guessing the print run correct is really only important for financial reasons. Printing has a steep economy of scale, so the more you print, the less the per-unit cost. Guess too low and you pay more than you might have; same with guessing too high. But print runs can be used for marketing purposes: now in its 18th printing!!! Sounds so impressive, right? But no one asks how many were printed each time. And there is no industry standard. So I could do print runs of 50, and have books go into their fiftieth printing within months. Be wary of "we can't stop going back to the printer for more copies!" claims. There is no industry assumption as to how many copies are in a print run.

Reporting Bookstore. A reporting bookstore tells BookScan how many copies of a title it has sold. BookScan is the Neilsen ratings of publishing: it records book sales. Authors can access it through Amazon author pages, if they have one. Anyone can buy an extremely expensive license and access it.

BookScan numbers are unreliable. According to their own description, they count about 85% of books sold. Not all bookstores report their numbers; those that do are called reporting bookstores. Truly savvy publishers and authors can attempt to flood the cashiers of reporting bookstores with their books. But in addition to bookstores that do not report sales to BookScan are a slew of other means through which people can buy non-reported books. A key to Belt Publishing's business model is enticing people to buy our books directly from our online store. We sell anywhere from 10%-50% of all copies of a book sold through our store. So Belt Publishing books will always show far fewer copies sold on BookScan than the actual number sold. That hurts us in some respects: booksellers and sales representatives look up numbers to decide whether or not to order a title, and how many, and our far-lower-than-actual reported sales may dissuade them from trying our books out. That's a risk I am willing to take.

Bug, Glyph. Here's how a conversation goes between editors and designers at Belt Publishing, discussing our city anthologies, in which we try to design some cool city-specific logo to use as section breaks. For our Milwaukee Anthology, we used the botanical garden domes; for St. Louis, the arch, and for Akron, the Goodyear blimp. "What should we use for the little thingy?" "Um, Anne, the little thingy?" "You know, the doo dad that we put inside essays. The squiggle. The squib." Apparently these should be called bugs, or glyphs. They are cute.

Front Matter and Back Matter. These are elements of a book usually not included in the manuscript. They includes, in the front, "matter" such as the copyright page, the half-title page, the title page, epigraph, dedication. In the back, it usually refers to acknowledgments, author bio, bibliography, notes. We often add the front and back matter to a book after a manuscript has been proofed, so if you want to play "find the typo!" read the front and back matter carefully. And then please do not email us to tell us what you have discovered until we are ready to send the book to the printer for a second print run, when we can make changes. Otherwise we will just have to live with those pits in our stomachs. Thanks!

Gutter. The inside margin of a page. Gutters become very important when one of the many authors-to-be, new designers, and overexcited editors decide to do that thing I hate: add images. Images are complicated in books! The web has made us forget this! Open up the book closest to you, one that without a broken binding, to the middle. Notice how it’s harder to open it all the way? Now imagine someone had decided to put a picture there. Or, even worse, an image that spreads across two pages. That’s right, the center of the two-page-spread image would be sucked down into the binding. Never forget the gutter.

Bleed. When you use images, consider the gutter as well the bleed—it’s a murder scene over there in the typesetting alley. A bleed is an image that extends to the edge of a page. A full bleed is an image that extends to the all the edges of a page. Gutters and alleys and margins all have to be carefully adjusted so the printer doesn’t trim off part of the image when binding. Images, they are hard.

Stet. Stet is a proofreading term. It tells the reader to disregard the change that a previous editor or proofreader has marked (equivalent to not accepting a change in Word’s track changes). The term comes from the latin verb sto and means “Let it stand.” One of my favorite/most abhorred phrases to use is “he stetted back all my changes!” It is also my favorite because it sounds so impressive. It is abhorred because it usually means I am working with a either an extemely particular or overly arrogant writer.

Bulk up the spine. I used this in conversation without trying the other day and I really proud of myself. I was talking about what kind of paper we would choose for a book, and I thought a thick glossy stock would work best. I said, “plus it would bulk up the spine,” and then gave myself a round of applause for sounding so fancy. A short book will have a thin spine—and sometimes a very thin spine is not a good thing : thin spines get lost on shelves, and it’s hard to print the title and author on less than 1/2 inches of space. So you can use thicker paper—or wider margins, or blank pages between chapters, or other tricks you remember from college when your research paper was short of the minimum number of pages—to bulk up the spine.

Drop cap. Drop caps are larger first letters of a chapter or section that extend more than one line. Drop caps are older than printed books. Even before Gutenberg, scribes would use them. Those very elaborate illustrated first letters of words in chapters in manuscripts, inculabula, and codices are drop caps. Their genesis is practical: until the late middle ages, reading was noisy: people read out loud; the words were as scripts to be enunciated, not individual words to be scanned. There were no spaces between words, and no punctuation, and no difference between capital and lower case letters (or, to be historically accurate, majuscule and minuscule), because the reader was speaking the words aloud to himself. Large initial letters to start sections or chapters were the only marker for readings, telling them to take a breath, shift gears, as a new topic was to begin. Eventually, silent reading became the norm, and was less rooted in orality, and other devices developed to help readers navigate a text, such as punctuation and spaces and, after printing, standarized spelling. Drop caps are a lovely vestige of early manuscript culture.

*A version of this glossary is included in So You Want To Publish a Book? and was first published in a 2019 (!) substack newsletter.

Big sale over at the Belt Publishing store; $5 books! Grab yourself one or twenty. If you are reading this for free and want to support my writing, go ahead and upgrade to a paid subscription.

Oh this was so fun to read. Get those F'n G's in here!!! Folded and Gathered.

Very interesting!